Trade

Nigeria’s new Lekki port has doubled cargo capacity, but must not repeat previous failures

Three-quarters of the world is covered by water and up to 90% of world trade is seaborne. Seaports and shipping are critical to the conduct of global trade. Africa has relatively few natural harbours that offer shelter and are deep enough to take big vessels. Along the Atlantic coastline of West Africa, for instance, natural harbours exist only at Freetown and Lagos. Consequently, artificial ports have been carved out of lagoon and river ports, which dot the coastline from Morocco to South Africa. Considerable capital and engineering know-how have been applied since the late nineteenth century to make African ports accessible to ocean shipping. Since the 1990s, African countries have engaged in a “ports race” to emerge as the shipping hub for their region. In this context, the recent completion of the US$1.5 billion Lekki Deep Sea Port in Lagos, Nigeria, is significant. Lekki is one of Africa’s top six ports. It is Nigeria’s first fully automated port, and its largest. It has more than doubled the capacity of Lagos’ ports, which had remained the same for 25 years. It will accommodate the world’s largest cargo ships and is expected to reduce cargo wait times from over 50 days to two days. Its modernity and efficiency are projected to make Nigeria a regional hub and boost the country’s GDP. It is envisaged to generate 170,000 direct and indirect jobs, billions of dollars in tax revenues for Lagos State and the host community, and a turnover of US$361 billion over the next 45 years. My work on the economic history of African seaports supports the view that the Lekki Deep Sea Port could serve as a pivot of local and regional development. The project should have multiplier effects on commerce, industry, agriculture and small-scale enterprises connected to it by various modes of transport. A combination of factors will determine its success. These include its capacity to meet the demands of shipping; its efficiency and competitiveness in the national and international contexts; the coordination of policies; the way transport modes work together; the state of the inland economies; and the application of technology. Nigeria’s port history In colonial Nigeria, significant port development took place between 1850 and 1950 for the economic benefit of Britain. Shipping was concentrated at a few ports during the world wars and the Great Depression (1929-33). But increasing imports and exports in prosperous times required more functioning ports to cope with the greater volume of trade. Lagos and Port Harcourt gained prominence because they had railway links to the hinterland. Port Harcourt was created as an outlet for the coal exports from Udi, near Enugu in eastern Nigeria, and the tin exports of the Jos Plateau. Lagos had become the leading port in West Africa following extensive harbour works between 1892 and 1914 when it welcomed its first ocean liner. It handled the bulk of Nigeria’s foreign trade right into the independence period. The civil war of 1967-70 compelled the adoption of a policy of port concentration at Lagos. Port congestion at Lagos was aggravated by the demands of post-war reconstruction. Massive oil revenues, following the 1973 Arab-Israeli conflict, funded massive imports. Poor planning saddled Nigerian ports with an armada of cement-laden ships in the late 1970s. The congestion imposed huge demurrage costs on the country. And containerisation, which existing seaports were unsuited to handle, made it necessary to expand Apapa Port and create the Tin Can port in Lagos in 1977. During the 1980s and 1990s, the growth of the national economy outstripped the installed capacity of Nigerian ports. At the same time, Nigerian ports attained increasing notoriety for inefficiency, decaying infrastructure, uncompetitive tariffs and systemic corruption. Other West African ports offered better services – so traffic went there instead. The Nigerian government eventually in 2005 adopted the landlord model of port administration: state control was replaced by a system of concessions. This improved port services, but did not bridge the gap between capacity and volume of container traffic. Thus the idea of the Lekki Deep Sea Port was conceived. Lekki port’s potential Lekki is expected to generate direct and induced business revenue estimated at US$158 billion, a qualitative impact on the manufacturing, commercial and services sectors, and a multiplier effect over 230 times the cost of construction. It will attract a massive influx of people, businesses and investment. The new facility will support the industrial and petrochemical complex, including the Dangote Refinery, the largest in the world, situated in the Lekki Free Trade Zone. It is poised to attract investment in the range of US$20 billion in the first few years. With an airport in the vicinity, the port will be a component of a Harbour City equipped with logistics infrastructure of various kinds. Lekki port should reduce congestion at the older ports in Lagos and help recover the lost traffic of landlocked Chad and Niger, which had been diverted to more efficient ports in the sub-region. The port also positions Nigeria to optimise the African Continental Free Trade Agreement. Weak Points However, it appears that the project suffered from some lapses in planning. Provision for cargo evacuation by rail is non-existent, and the road infrastructure is inadequate for the anticipated volume of traffic. The other challenge is the encroachment on land around the Lekki port and the future problem of congestion. Unless the state government takes drastic action under the Land Use Act to acquire land in the public interest for the future expansion of the port, it will be a repeat of the problems of older ports hemmed in by unplanned industrial, urban and commercial land use. The project indicates that public-private sector partnership is the best way to plan and deliver landmark infrastructure projects. Lekki Port LFTZ Enterprise Ltd was created for the purpose, with investment by China Harbour Engineering Company Ltd, Singapore’s Tolaram Group and the Nigerian government. But it has the potential drawback of idle capacity if the economic prospects that motivated it fail to materialise. Then the huge investment in the deep sea port project would become a huge burden of unpaid debts. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Read more »

BUA Foods: Why Bet on Nigeria’s Newest FMCG conglomerate

Nigerian capital markets started 2022 with an injection of NGN 720 bn ($1.8bn) following the listing of BUA Foods on the main board of the Nigerian Stock Exchange (NSE). The new company is the result of the consolidation of several of Abdulsamadu Rabiu’s businesses under BUA International, a conglomerate he founded in 1988. While BUA Cement listed in January 2020, several of the group’s other verticals remained unstructured, including sugar refining and plantations, rice, flour milling & pasta production, oil & gas, construction, real estate and logistics. With BUA Foods, Rabiu is betting on Nigeria’s agriculture and fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) market by consolidating its sugar, rice, flour, pasta and edible oils business into one single entity. BUA Foods combines assets worth almost NGN 650 bn and had generated over NGN 300bn from January to November last year, with a net profit of almost NGN 80 bn. Some of the country’s best institutions were mobilized on the listing operation, including Udo Udoma & Belo-Osagie as solicitors, Stanbic IBTC Capital as lead financial adviser, Rand Merchant Bank Nigeria and UCML Capital as joint financial advisers, APT Securities and Funds and CardinalStone Securities as joint stockbrokers. For investors, BUA Foods offers an interesting and diversified exposure to Nigeria’s FMCG market, expected to grow on the back of strong demographics and a projected population of over 260m by 2030. However, for Rabiu and the entire BUA Group, the challenge is now on navigating the country’s sluggish economic recovery that has left consumer spending at very low levels on the back of historic inflation and rising poverty. In this context, BUA Foods’ confidence comes from its investment into some of the country’s most basic and needed goods. Despite a weak consumer disposable income and high poverty rates, the case for the growth of Nigeria’s consumer goods industry remains compelling. This is notably the case for staple foods such as bread, pasta, rice and cereals where growth is modest but positive even in the short-term. BUA Foods also has policy on its side. Through the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), the government has constantly sought to boost local output by restricting access to foreign exchange for dozens of imported items. These notably include food and agricultural products such as rice, palm oil, vegetable oil, and margarine – precisely the ones the company is investing in. Betting on import-substitution with sugar In sugar, BUA Foods now gathers the Apapa and Port Harcourt sugar refineries with a total refining capacity of 1.5 million metric tonnes per annum (mtpa), along with 70,000 ha of plantations in the states of Kogi (Bassa Sugar Co.) and Kwara (LASUCO Sugar Co.). With such assets, Rabiu wants to be part of the execution of the Nigerian Sugar Master Plan (NSMP) that seeks to cut sugar imports and grow local output. BUA Foods’ new sugar division is notably expected to commission this year a new 220,000 tonnes per annum (tpa) sugar refinery on its LASUCO plantation in Lafiagi (Kwara) with a daily crushing capacity of 10,000 tonnes of cane per day (tcd). The refinery will also be able to produce 20m litres of ethanol a year, and 32 MW of electricity from bagasse, making it Nigeria’s most integrated sugar complex. The project received a $200m boost from the Africa Finance Corporation last year, and remains one of Nigeria’s most ambitious and vertically-integrated facility. Positioned for long-term growth in flour In flour, BUA Foods will need to operate in a market where demand has been heavily impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic but where long-term growth fundamentals remain robust. The market remains heavily marked by imports of wheat and is dominated by well-established players such as Flour Mills of Nigeria, Honeywell Flour Mills and Crown Flour Mills (Olam). To compete and grow, BUA Foods’ flour division can rely on a flour milling complex in Rivers State with a capacity of 500,000 tonnes per annum (tpa). The facility is currently being expanded to 1.3 mtpa by Turkish contractor Milleral Integrated Millin Systems, with commissioning expected no later than this year. On the verge of leadership in pasta In pasta, BUA Foods inherited from an industrial complex in Port Harcourt made of one pasta factory plant with a capacity of 250,000 tpa. This is currently being increased to 500,000 tpa with the addition of a second factory built by Italian contractor FAVA. Upon commissioning, it will make BUA Foods Nigeria’s second-largest pasta producer. While rice dominates the Nigerian market, pasta consumption has been on the rise and Fitch Solutions notably forecasts market revenue to to experience double digit growth until at least 2026. Ambitious expansion plans in rice In rice, BUA Foods is constructing a rice milling facility with an initial capacity of 200,000 tpa, and a rice plantation of about 10,000ha in Kano. Both assets will make the company the largest rice milling business in Nigeria and are expected to start operating this year. With rice, Rabiu bets once again on an attractive import-substitution business. Rice is the third-most consumed staple food in Nigeria after maize and cassava, but while Nigeria is Africa’s second largest rice producer, it is also the world’s third largest rice importer. Moving forward, the company wants to expand its rice milling business to a combined 1 mtpa with the installation of new rice milling facilities in Gujungu (Jigawa State) and a rice mill and plantation in Agaie (Niger State). While the market is dominated by the likes of Olam International, TGI (Wacot Rice) and Stallion, the size of the cake is big enough for everyone. However, BUA Foods’ success will depend on its ability to improve seed quality and adopt better farming techniques to support output growth and competitive margins. An ambition to resuscitate a defunct edible oils business In edible oils finally, BUA Foods inherits from two palm oil mills in Kano and Lagos with a capacity of 250,000 tpa. However, neither facility is operational and the new edible oil division is expected to resuscitate them by 2024

Read more »

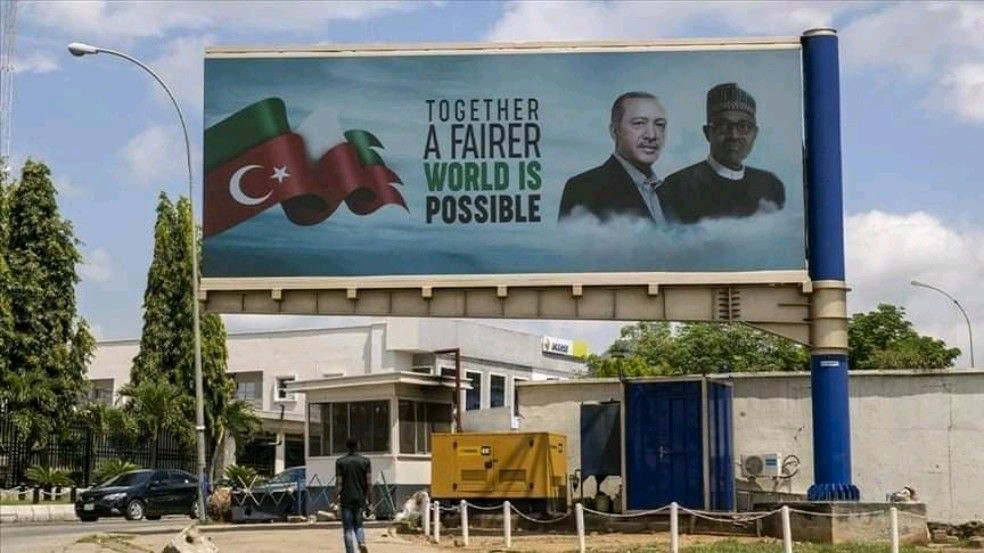

Erdoğan’s African tour: a win-win partnership?

On Sunday, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan began his African tour which will take him to Togo, Nigeria and Angola. The visit will marked by trade and security agreements, but it also takes place in a context of tensions involving other powers, in particular France. This will be the 15th time Erdoğan has stepped on African soil as Turkey’s top leader. As President, he has done several short, but regular, journeys which began in 2004 when he was still Prime Minister, and which saw him visit, among others Ethiopia, Tunisia, South Africa, Libya, Somalia, Niger, Senegal and Ghana. By the time he completes his ongoing visit, he will have been to 30 African countries. These relational approaches are far from unilateral, since one notes, for example, that the last 5 presidential visits received by Turkey are African (Angola, Guinea, Sudan, Ethiopia, DRC). Erdoğan also received two weeks ago, Moussa Faki, president of the AU Commission. The discussions focused on issues of infrastructural, economic and human development, mediation, culture, trade, and also humanitarian aspects. In fact, the bilateral trade volume between the two parties has practically increased fourfold in 18 years, going, according to the Turkish Ministry of Commerce, from $ 5.3 bn in 2003 to more than $20 bn today. Turkish investments have also grown in Africa in recent years, going from $ 100m in 2003 to $ 6.5 bn in 2017 (infrastructure, schools, hospitals, etc.). At the same time, the number of Turkish embassies in Africa has increased from 12 to 41. The arrival yesterday of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan precedes the 3rd Turkey-Africa Cooperation Summit which will be held from October 21 to 22 in Istanbul and which will bring together the 54 countries of the continent through official representatives or the private sector. It will be followed on December 17th by the 3rd Turkey-Africa Partnership Summit. The multiplication of African embassies in Anatolia and flights between the two destinations will greatly facilitate things. In the meantime, there is talk of reaching a trade volume of half a billion dollars between Turkey and Angola (currently $ 116 m), along with progressing joint counterterrorism initiatives and executing agreements on hydrocarbons and energy with Nigeria, then economic and defense agreements with Togo.

Read more »

In Kyé-Ossi, a women-led trade fair encourages regional integration

Authorities in three Central African countries of Cameroon, Gabon and Equatorial Guinea, officially launched the annual CEMAC Cross-Border Fair (FOTRAC) In August with the aim of stimulating economic activities in a region hard hit by the Covid-19 pandemic. Spread over ten days, the fair in the CEMAC zone is organized in the Cameroonian city of Kyé-Ossi, which shares borders with the three countries. The activities of the fair take place under the theme “Relaunching intra-regional trade for peace, the socio-economic and cultural development of Africa despite the Covid-19”. “This is the post-Covid-19 edition of the show. We closed our borders when the pandemic was at its peak and it did affect cross-border trade. We hope that this edition of the fair will significantly revive economic activities now that the borders are open,” Félix Nguelle Nguelle, governor of the southern region of Cameroon hosting the event, told reporters. For the organizer of the event, Danielle Nlate, also president of the Network of Active Women of the Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa (REFAC), the fair will strengthen sub-regional integration within the framework of the free movement of people and property in the area. Note this year the presence of all 11 ECCAS countries, the Economic Community of Central African States: Angola, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo, DRC, Gabon, Guinea Equatorial, Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, and Chad, in addition to Senegal.

Read more »